Context & Problem

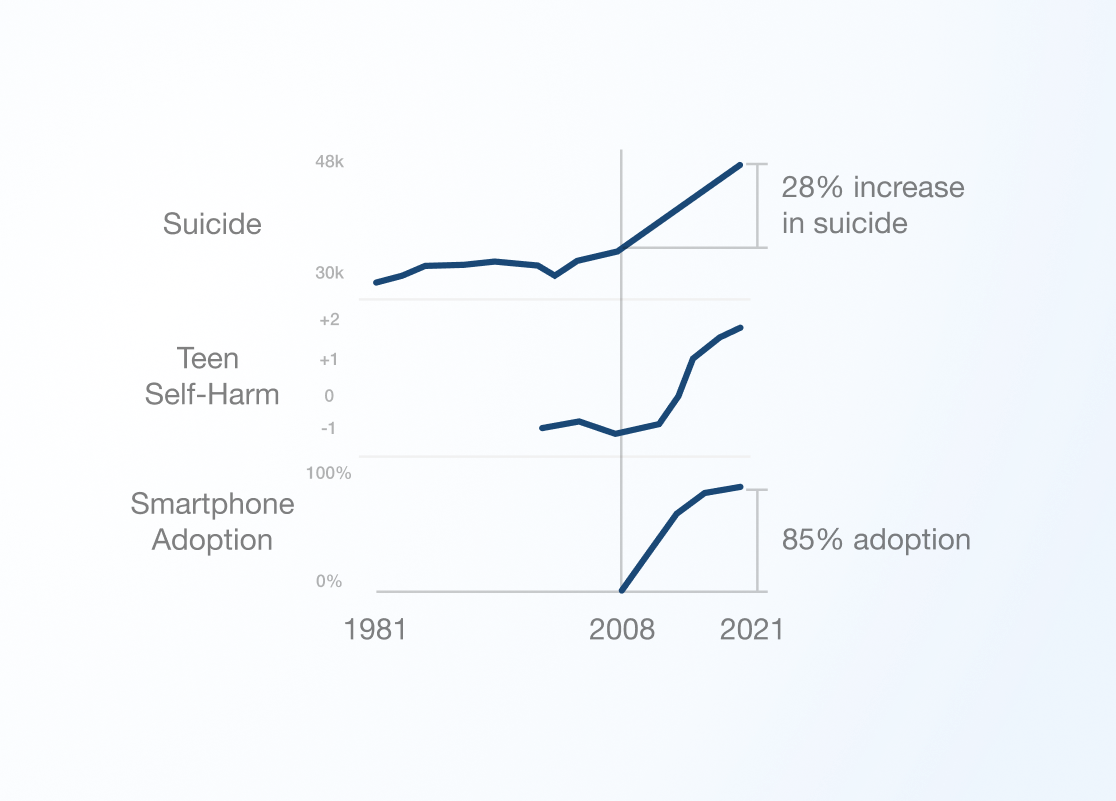

The initial indicators of a potential problem were evident - smartphone adoption and usage time increases correlated with national mental health issues.

To identify if a potential problem really existed, I conducted over 50 interviews with phone users, across age and lifestyle demographics. I reviewed APHA and NIH mental health downstream metrics such as rates of teen self-harm and national suicide rate, along with smartphone screen time statistics on the same timeframe.

Even considering COVID-19, the 2008 financial crisis, and other systemic factors with scale, the trends following adoption are sustained. While these correlations cannot on their own prove causation, the persistence and scale of the patterns suggest they warrant deeper, more formal research.

SIMPLIFIED STATISTICS FROM US DHHS, APHA, AND DR. JEAN TWENGE

In user interviews, no users had found a lasting and effective solution for themselves.

They could outline their own specific problems clearly, which followed the pattern of “I use X app at Y time of day too much”. However, no interventions they tried worked, from built in screentime monitoring to custom blocking apps. They also did not understand why these solutions failed.

Competitive analysis painted a picture of what wasn't working, but what could work.

Meditation apps like Headspace were the go-to for users, however with a 93% 30-day churn they were an ineffective long-term solution. These solutions had fundamental problems, as illustrated by their CPO.

QUOTING A 2022 LECTURE FROM LESLIE WITT, HEADSPACE CHIEF PRODUCT OFFICER

However, in other markets products like Noom (market cap $3.7B) painted a picture of how positive health outcomes could be achieved through a digital service, using education and behavioral change.

The case for initial investment was strong.

The scale of the problem, the reasonable potential for a novel and effective solution, and the appetite consumers displayed were all signals that this was worth pursuing.

Strategy & Collaboration

I assembled an advisory board over time, consisting of CMU professors, successful entrepreneurs, and venture capitalists.

The advisory board spanned psychology, design, engineering, and business. The Carnegie Mellon Swartz Center, within the Tepper Business School, partnered with my company early on to provide us with office space, connections, and resources. Advisors were instrumental in steering research and product development at every juncture.

Early on, psychology advisors were instrumental on refining problem definition and intervention approach. In particular, the initial design strategy shifted greatly after a discussion with the Chair of the Psychology Department. This discussion explored the question: “What is a reasonable to expect the user to be capable of, in regards to shaping a solution for themselves, and what is unreasonable?”

Beyond psychology, business and VC advisors challenged whether a product was viable, and guided defining markets and strategy. Design advisors at CMU and in industry were involved in critique at each iteration.

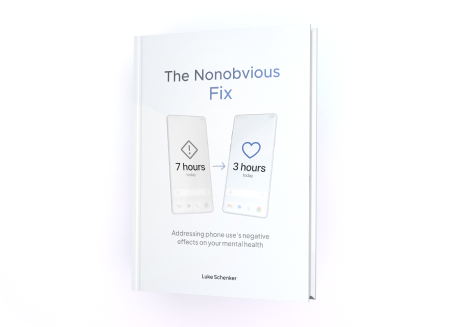

To formalize the problem, I first created a simple model of how screentime influenced mental health over time.

The model looks at the phone and user as a symbiotic relationship. The user engages the phone, and the phone responds. The phone engages the user, and the user responds. The sum of both of these engagement avenues constitutes the total screentime for a user.

Therefore, as the phone engages the user more, use increases. As the user engages the phone more with a growing number of habits, use increases.

As use increases, two general categories of problems arise which contribute to anxiety and depression:

-

Users spend less time present in real life, reducing opportunities to adjust, process and adapt to situations, and self-regulate.

-

Increased screentime gradually exposes them to more emotionally intense content, distorting self-image and creating an exaggerated negative view of the world.

This explanation is heavily simplified for this case study - request my book for greater depth.

Based on that model, I identified a number of hypotheses on how to address negative mental health influence.

We hypothesize that problems arise from increased screentime. However, reducing smartphone features can also negatively impact the users ability to function in daily life. So, the questions we have are:

-

“How can we reduce unwanted overuse, while not impeding utility?”

-

“Does reducing unwanted use measurably impact mental health?”

Based on our model of the problem and our hypotheses, I created a product strategy and underlying design principles.

Design principles:

-

User habits are shaped by consistent environmental influence.

-

Users do not clearly understand how phone use negatively effects mental health over time.

-

Users are willing to sacrifice if they gain something they value more.

-

Unwanted use was defined by a specific app, at a specific part of the user's routine.

-

Unwanted use's definition is specific to the individual, and varies widely.

-

Deep understanding of user need cannot be automated, and must be user-directed.

-

Habits are automatic once established, and need to be disrupted to be changed.

Based on these ideas, the product strategy took shape as a number of features that reflected these principles, and could be used to reduce unwanted overuse.

Solution features:

-

Apps, websites, and notifications could be blocked at specific times of day.

-

User homescreen interface would change the appearance of icons to break engagement habits.

-

Users would set goals for their lifestyle that they valued, which would inform what apps detracted from that lifestyle.

-

Users would be educated on how their phone can influence negative mental health outcomes over time, to inform their decisions on what to limit.

-

Environmental consistency changes behavior over time, so the user's ability to change their phone settings and limits requires friction and intermittent inaccessibility.

Constraints & Execution

Due to a potential solution's minimal scope being significant, I targeted government, foundations, and venture capital to raise a seed round.

I pitched a panel of doctors at the National Institute of Mental Health, sent grant proposals to the National Science Foundation and additional private institutions, and applied to and pitched venture capital firms. I discovered varying interest in the problems I illustrated, but ultimately it was clear that a product would be needed to raise capital.

Without funding, I outlined an MVP and a research study which would act as a go/no-go point.

Given the potential in the solution's approach, there was a strong case to bootstrap the production of an MVP. To make the case beyond an MVP, it had to have measurable positive mental health outcomes. This meant it required a study that used clinically recognized measurements of mental health conditions, specifically anxiety and depression.

If results were not significant, the project would be killed.

Due to significant constraints, the MVP feature set and implementation balanced highest impact features, with survivable tradeoffs.

Given the model we established for the user-phone relationship, there were a number of features that could be impactful towards enabling a user to modify their device to change their usage habits.

For example:

-

Feature parity with homescreen usability standards (drag/drop apps)

-

Homescreen support of widgets.

-

Modifying UI patterns in existing websites that triggered unwanted overuse.

These features may have had an influence on treatment outcomes, but did not have as strong of a basis as the core features chosen, which mapped directly to findings in interviews and research.

Tight constraints also influenced the design and engineering strategy.

I designed the setup user experience on desktop, which allowed the user to then use their customized device on mobile. This expedited the design process, and designing for desktop provided a larger form factor which required less states/nesting than mobile design. This sped up development as well, as I had a stronger familiarity with web front/backend than mobile application development.

Solution

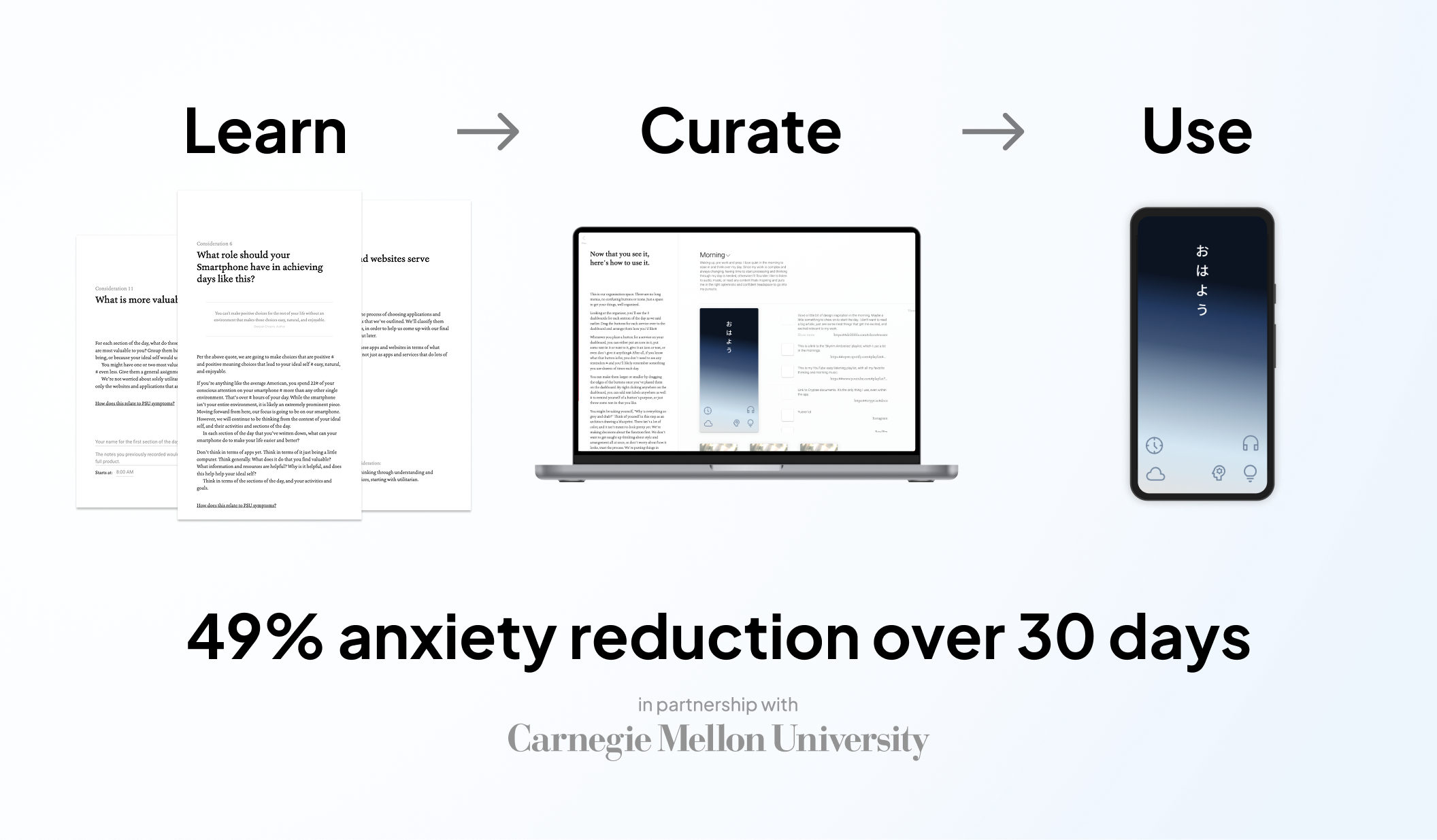

The solution's initial design was a smartphone accurately curated to the user's daily routines.

The phone would have different homescreens, and different apps available or unavailable during different parts of their daily routine. In essence they'd be using what felt like a different phone during the workday, a different phone during the evening, sleep, etc.

This design and treatment strategy was based on interviewee feedback, and input from advisors in Carnegie Mellon's psychology and design schools.

RENDERS OF PRODUCTION UI SCREENSHOTS

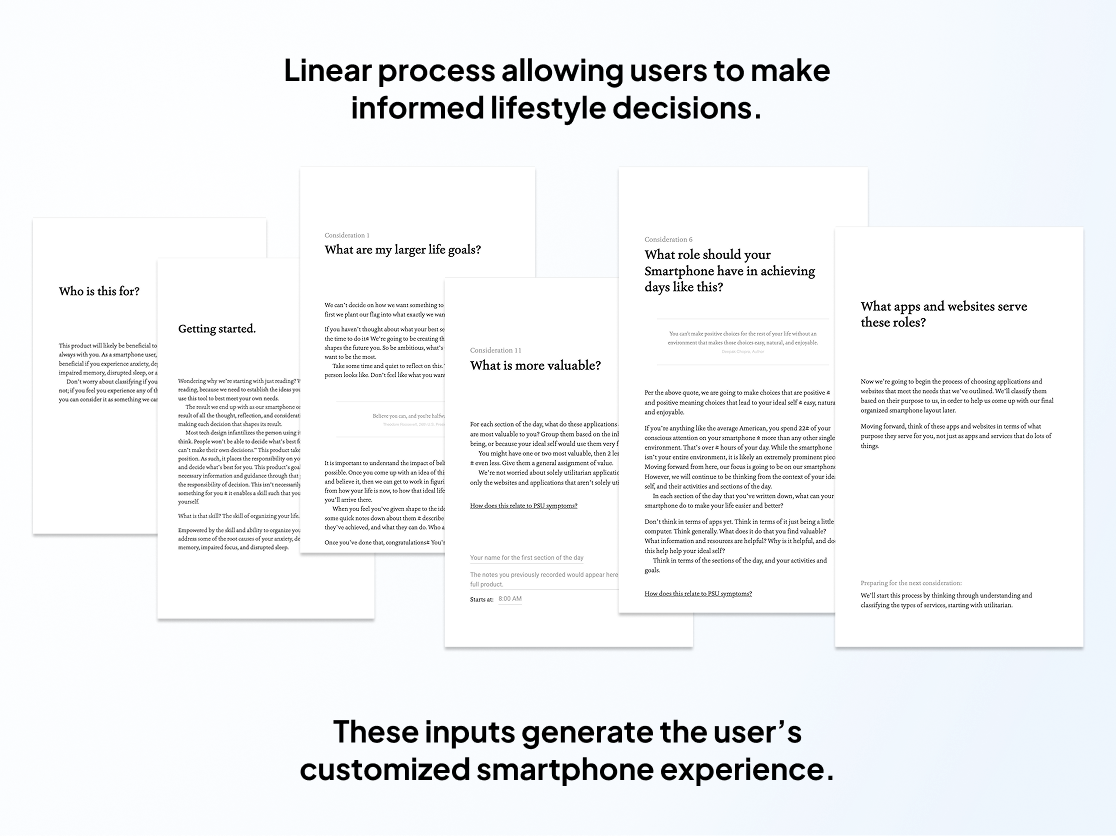

The user would go through a linear goal setting and decision making process. This would establish what the phone could be used for, and when, aligning with their routine needs.

Users were easily able to identify what apps caused their unwanted overuse, and when that overuse took place. So, making decisions to omit those applications from different parts of the routine was simple.

This decision making process was paired with education about phone influence and mental health.

SAMPLES OF THE PILOT PRODUCT'S ORIGINAL ONBOARDING

The MVP was lean, but designed to provide high integrity study results.

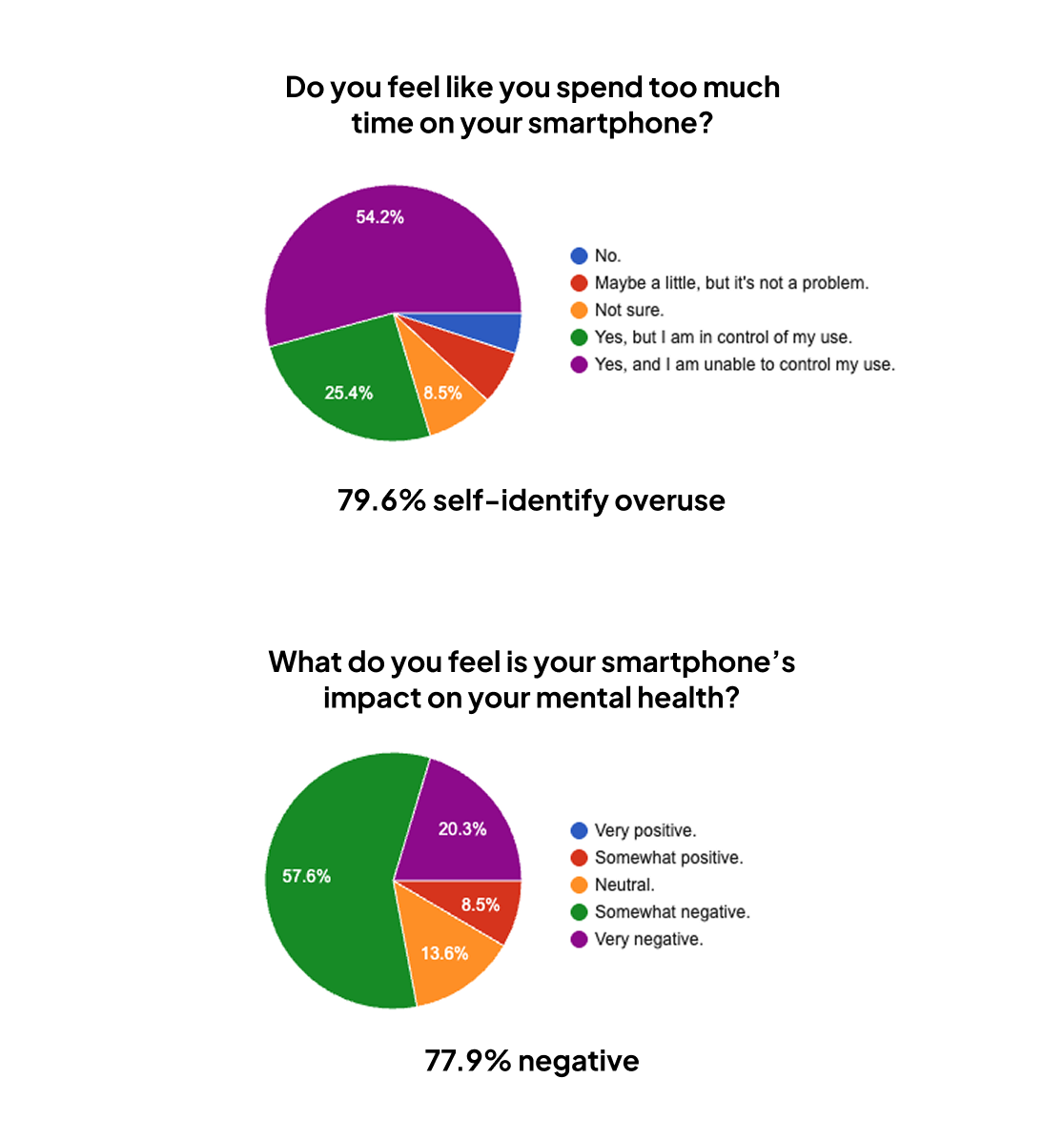

To measure the MVP's performance, I deployed a study at Carnegie Mellon with the student body, in which I partnered with Counseling and Psychological Services (CaPS) to advertise the study.

Applicants for a spot in the study first filled out a survey, which I designed to identify their severity of need, interest, and applicability. Out of 60 applications received in just the first week, I selected 5 to participate in the study.

SURVEY RESULT SAMPLE FROM STUDENTS AT CARNEGIE MELLON

Students used the product for a month, completing numerous assessments measuring changes in behavior and mental health.

A blend of research methods were used to learn as much as possible about the users' experience.

UX and behavioral research methods:

-

Targeted questionnaires on different aspects of the product experience.

-

Interviews about their experience.

-

Daily Journals users completed outlining how they felt, and their perceived changes.

Mental health research methods:

-

Assessing depression and anxiety indexes as the start and end of the study (BDI-II, GAD-7)

Throughout the study, I actively supported and interviewed participants.

All users were able to contact me easily with questions and issues. Many times unplanned conversations became interviews in which we'd discuss how their lifestyle was changing, and how they felt.

At the closure of the study, I distilled psychological and product research findings.

Given the significant volume of content produced by my study design methods, I created a “research atlas” that organized the findings categorically, and identified patterns in findings and outcomes.

The atlas was designed to make further product design simple by making findings accessible, but also allow new team members to easily explore the research and understand the users.

Impact

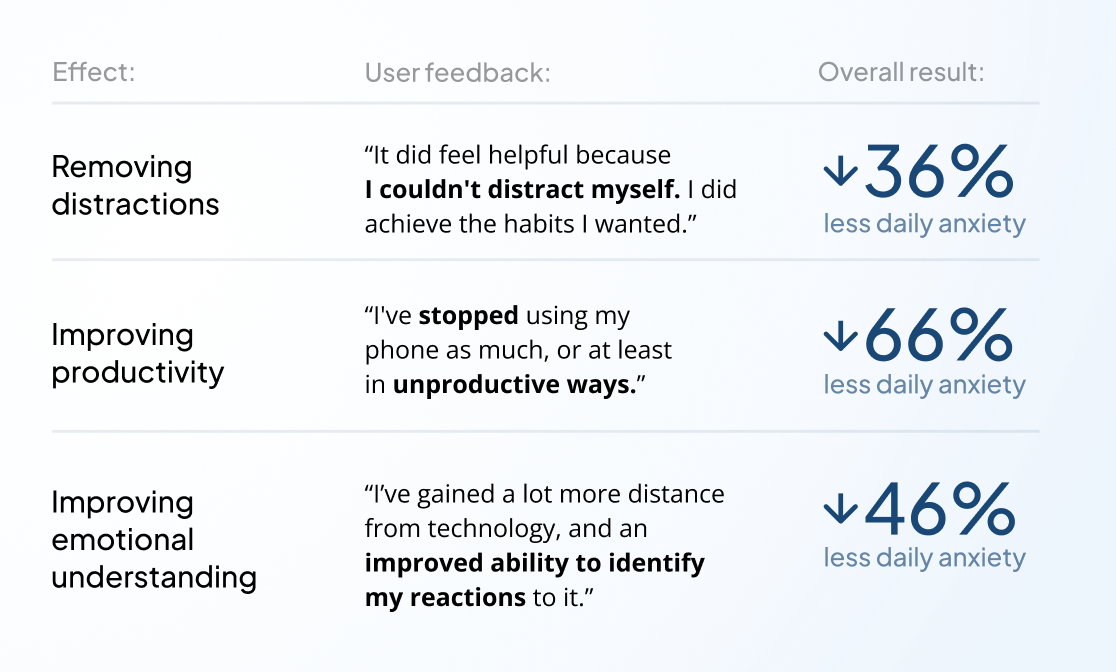

Findings illustrated what was effective, why, and provided a confident path forward.

The most dramatic finding was a 49% decrease in anxiety on average across all users, with one user achieving a 66% decrease. Every study participant’s anxiety severity dropped categorically - users with severe anxiety now had moderate, users with moderate anxiety now had mild, and users with mild anxiety had minimal. Those degrees of change have dramatically beneficial implications over time.

GAD-7 SELF ASSESSMENT AVERAGE ACROSS STUDY PARTICIPANTS

USER INTERVIEW QUOTES AND ANONYMIZED STUDY RESULTS

That decrease along with qualitative user input provided a clear picture of how that result was achieved.

There were plenty of issues with the pilot product's approach, but the fundamental treatment and design strategy had significant wins.

-

Education and goal setting were extremely favorable and effective.

-

User-directed and informed decision making resulted in effective self-treatment.

-

Planned app and notification restriction based on routine was effective at behavioral change.

-

Altered homescreen interface supported breaking existing habits.

Even these wins did have issues. Education and onboarding felt too long, homescreen customization user experience was clunky, changing app restrictions had too much friction which sometimes compromised benefit, and more. Importantly, all these issues were largely product experience problems that could be addressed. There were no significant issues with the fundamental treatment strategy.

The largest problems stemmed from splitting the user experience across desktop and mobile, both in regards to user experience and technical issues. While this was a necessary tradeoff to expedite the MVP, the product would need to be unified on mobile to be viable commercially.

These results de-risked further investment, which in combination with other signals made a confident case to move forward to commercialization.

-

We're aiming at a recently emergent problem in the market.

-

We have a novel product with established high treatment efficacy.

-

We have a motivated potential user base actively searching for solutions to the high-value problem the product addresses.

-

The market size of our potential base is favorable, at 29M in the US, and 21M in the EU (users who have diagnosed anxiety disorders, and use Android devices in accessible markets)

-

Even without funding, operating costs (research, design, deployment) could be managed to enable commercial production.

Based on these factors, and the research findings, the case was made to improve the product and expand the team.

Read the commercialization case study to learn more about how this product strategy was taken forward, and the internships case study which outlines the building and management of the team.